“Screening Pakistani films has opened a window for us [in India] across the border,” Salma Siddiqui told The Express Tribune.

Brought up in Dehli, Siddiqui is currently pursuing a PhD in Media Art and Design at the University of Westminster in London. She was presenting a research paper at the Institute of Peace and Secular Studies (IPSS) on Friday on her fourth visit to the country since 2000. She had visited Islamabad and Karachi on her earlier visits.

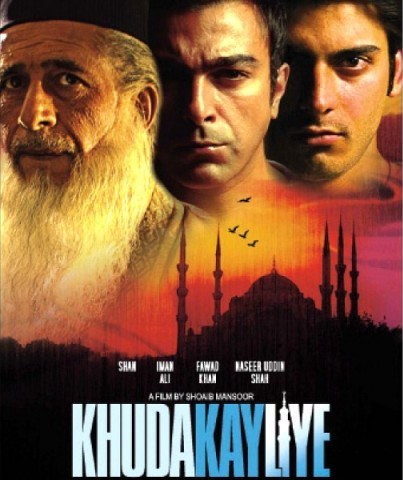

Her paper, published by the Academy of Third World Studies at the Jamia Millia-e-Islamia in Delhi, where she completed her Masters in Philosophy, examines the construction of history and identity in contemporary Pakistani films by analysing three films: Khuda Ke Liye, Khamosh Paani and Ramchand Pakistani.

Siddiqui said the political comes into contact with the personal in these films. “Identity is contingent on political events,” she said. “For example, in Khuda ke liye, the identity of Fawad Khan’s character is contingent upon the political context in Pakistan.”

“Films are an important source of history,” she said, “All three films push its boundaries.” She said Walter Benjamin’s edict that ‘contemporary crises can be articulated by reference to earlier crises’ stands true for the art of film making.

Narrating the reaction of Indian audiences upon watching Ramchand Pakistani, Siddiqui said, “In India, people were surprised that a non-Muslim could be a Pakistani.” The film’s protagonist, a Hindu boy who crosses into India by mistake, narrates a story about a member of a marginalised community in Pakistan, she said.

She said every filmmaker has their own purpose behind creating a film. “Ramchand Pakistani director Mehreen Jabbar was inspired by an actual incident while Khuda ke liye director Shoaib Mansoor said his film was an expression of his personal outrage at his friend Junaid Jamshed’s transformation from a ‘musician to a radical’,” she said.

“Speaking from the position of an Indian Muslim who watched Khuda Ke Liye, I thought the movie made some bold and interesting statements,” Siddiqui said. “It argued that the terror timeline in Pakistan started before 9/11.”

She said the movie addressed both growing radicalisation of the Pakistani society and rising Islamophobia in the rest of the world. However, Saeeda Diep, the IPSS chairperson, said the film took an apologetic tone about religious radicalisation in the Pakistani society. She contested that the film had tried to link radicalisation in Pakistan to events in the outside world.

Speaking about similarities in the three films, Siddiqui said the protagonist in each was depicted as “an idle and naïve male.” She said the protagonists reflected the heterogeneity in the Pakistani society. She said, “Another similarity is that the love relationships in the three films cut across religious, ideological or geographic boundaries but fail at the end.”

“The three films acknowledge taboos in society about such relationships, and portray that they are bound to fail,” she said. She said a “fankaar” [artist] was depicted in all three films, which provided an insight into the prospects of those with creative and artistic abilities in the country. “While all other identities in the films are hyphenated, the artist is free from these,” she said.

Gulnar Tabassum, a documentary filmmaker, contended that the films under discussion were not made for local audiences. “The funding and production aimed at projecting a certain image of the society instead of focusing on filmmaking,” she said. Anmmar Rasool, an advertising professional who has studied filmmaking, argued that the films reflected art too, which was why they became popular.

Speaking to The Tribune after the talk, Siddiqui said, “Khuda Ke Liye did well in India because no such film had come out of Bollywood,” she said.

good lollypop for pakistan.. n pakistani crazy for indian lollypop.. shame on