“We need the pain…because somewhere in that pain… lies the person that we have lost…and without it…we lose them completely.”

And that’s exactly when I teared up; tears not caused by sadness or grief — tears full of hope!

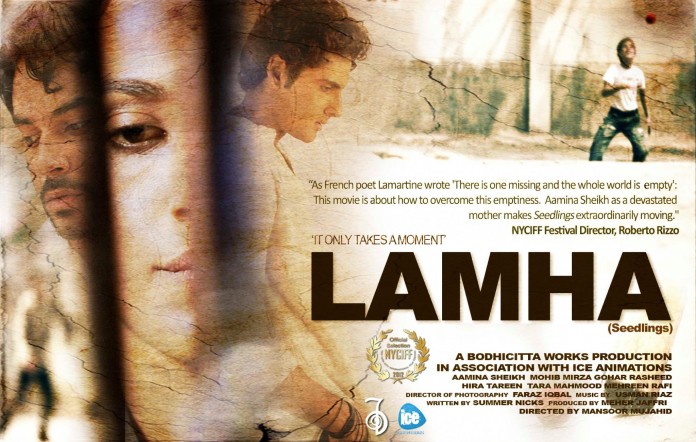

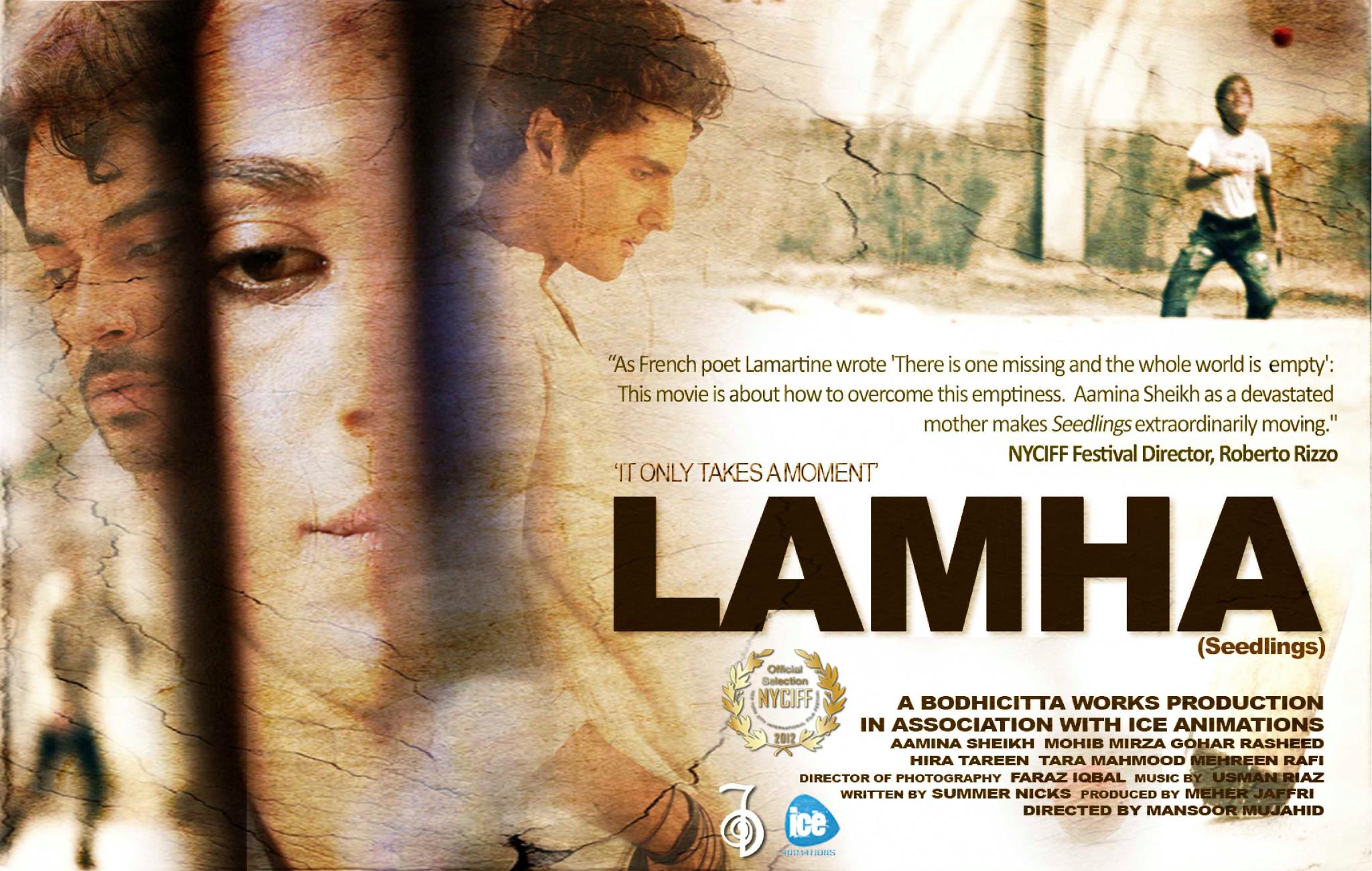

I really can’t remember the last time I cried in a film. However, last week, I was moved by an independent film from Pakistan calledSeedlings (Lamha).

An avid indie movie aficionado, I was excited to hear about a local film from Pakistan playing at the New York City International Film Festival. I bought tickets for myself and a co-worker just in the nick of time because they were soon sold out thanks to all the DAFNYs (Desi Artsy Fartsy New Yorkers).

There were a handful of celebrity sightings at the venue, which included leading stars from the film. We stood in a corner for a few minutes to gaze over the bulky cameras of Geo and Voice of Americato spot any red-carpet faux pas or cute outfits. One of the male stars from the film was brave enough to sport a military-esque sherwani with a Jinnah cap and I thought that made a pretty solid and impressive fashion statement. After a decade in the city of rebellion, I am a sucker for avant garde fashion!

As the lights dimmed and the opening scene began, I was immediately engrossed. The first scene was simple yet beautifully shot. As the camera zoomed up on the female lead, I too found myself being pulled into Maliha, Raza and Anil’s world. Let me add, if you’re expecting a film with a plot rich in twists and turns, this may not be for you. Yet for me, that’s exactly what made the film so enjoyable — its realistic simplicity, the simplicity of the story, the simplicity of its execution and dialogues.

Raza (played by Mohib Mirza) and Maliha (Aamina Sheikh) are husband and wife, who once probably lived the blissful life of a love-struck Karachiite couple. Their world was probably once full of artistic effervescence; as vibrant as the painted strokes on Maliha’s canvas or the colourful images from Raza’s creative photographs. But when the movie begins, you are introduced to them a year after their son’s unexpected death. All the imaginative colours and the inspiration from their lives have since perished and been replaced with heart-wrenching pain.

There is no heavy make-up to take away the credibility of their present lives. You see every blemish, every crater and every imperfection. Despondent hues and dimly lit scenes help validate the morose tension that has permeated into every crevice of their house; their awkward and almost painful interaction with each other is convincing — exactly how it must feel when faced with the uncertainty of holding on but not knowing whether to let go. All of this is shown brilliantly through carefully crafted scenes remaining true to the visual versus verbal aspect of good film-making.

The performances of all the actors — not just the leading three — are extraordinary. Special mention should be made about Gohar Rasheed who played Anil, the frustrated rickshaw driver. There are also some other noteworthy scenes in the film like the part where Maliha finally vents out her anger at Anil not just with rage but in cathartic hopes of closure and resolve. However, my favourite scenes came at the end of the film: the ones that carried a message of optimism. And amazingly those were also the moments that made my vision blur up with tears. The movie ends on a very uplifting note and that is when I realised that in the past two hours, we have not only been introduced to but have connected with more than just the three main characters in the film. Everyone searches for closure in the end — all the characters in the film, even the members in the audience.

Lamha could initially be perceived to be about how lives can change for the worst in just a moment. But by the end, one wonders if the “lamha” in the film is the one within our control, the moment we finally take the first step to moving ahead and moving on.

More work from the writer can be read at iampadash.blogspot.com